Pumped Storage Hydropower a "game-changer"

A series of Pumped Storage Hydropower (PSH) projects planned across 5 states could triple Australia's electricity storage capacity, according to a new study by a researcher at The Australian National University (ANU).

Professor Jamie Pittock says if the projects go ahead, they will accelerate our transition to renewable energy.

"We're talking about more than 20 projects being assessed or built. This would put us well on the way to having a national grid that could rely almost entirely on renewables," Professor Pittock says.

"It's really a game changer. It destroys any argument that solar and wind can't provide the baseload power needed to keep the lights on in eastern Australia."

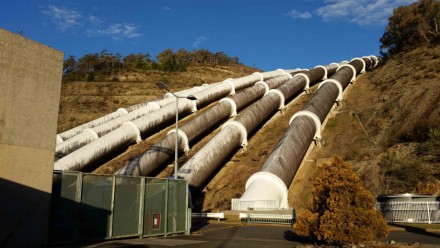

PSH works by having two connected reservoirs. When there is excess power, (for example, on especially sunny or windy days) it's used to pump water uphill.

During times of greater demand, power can then be generated by releasing water back down to a generator.

Professor Pittock's paper outlines the environmental implications of this system. He says it does throw up some unusual challenges.

"A lot of people live in rural areas because they don't want to live next to a big industrial project, it might be a shock if somebody suddenly turns around and says they want to build a reservoir on top of the nearest mountain."

A lot of high elevation areas that would otherwise be suitable have to be ruled out because of national parks or cultural sites. Other sites are too far from water or existing electricity transmission lines.

Professor Pittock says the sites which could soon be home to PSH projects include everything from old quarries, to doubling existing pumped hydro schemes and a "green" steel mill.

"One example is the old gold mining tunnels under Bendigo in Victoria, so sucking the contaminated water up to the surface and feeding it back down the mine shafts," Mr Pittock said.

In South Australia, another project proposes the use of sea water to generate power.

This means there's no blanket rule when it comes to sourcing the water needed for PSH.

"In South Australia for example, one project will buy water entitlements out of the Murray Darling Basin system."

"Then you've got Snowy Hydro, whose operators say legally nothing changes, we're using the same water, we're just recycling it."

Mr Pittock says despite the complexity, a number of the proposed sites are really promising, and more than enough to back up the grid.

"Estimates are that we would need about 20 big PSH facilities to back up the entire national grid. It's partly a judgement call about how much risk you want to take in terms of the reliability of the electricity supply."

The research has been published in Australian Environment Review.